There is a smooth stretch of concrete drive outside Luis’ house, but Armando never parks there. He leaves his white truck parked on the curb—a truck he could have only dreamed of owning in Mexico—and retrieves the mail from a rusty but dignified mailbox before rounding the side of the house to greet his son.

Luis zings toward Armando, pedaling furiously down the drive on his modified tricycle with its custom hand pedals. “Papito! Mira!” (“Father! Look!”) He is dressed in black, despite the Texas heat: trousers and a t-shirt with a silver Superman motif.

He stops inches from Armando with a happy screech, reversing his hand motion to brake with practiced expertise. Luis has owned the shiny blue bike for over a year and doesn’t bother strapping his feet in anymore. The word “DISCOVERY” is emblazoned in several places across the frame.

“He’s always optimistic. He helps find a solution for everything. He’s way ahead of us.” — Esmeralda, Luis’ mother

On a day like this, when the San Antonio sky is overcast and not so stifling hot in the late afternoon, Luis does laps in the driveway (with his mother’s help) until his dad comes home. He is now 13 years old and he first developed symptoms of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) at four, but was not accurately diagnosed until the age of six.

“¿Qué traes, Papa?” (“What do you have there, Father?”)

Armando grins and holds up a plastic bag with a gleaming pint of ice cream visible through the thin plastic. “Después de cenar!” (“After dinner!”) He laughs and leans in, resting his forehead against Luis’ for a moment before heading inside.

DMD is a hereditary disease which mostly affects boys and begins at an early age. Luis’ kindergarten teacher was the first to point out how frequently he fell and how certain gross motor achievements were harder for him than the other children.

But growing up in a hardscrabble neighborhood of San Luis de la Paz in Guanajuato, Mexico, doctors weren’t necessarily trained to recognize or identify the symptoms of this rare disease. Luis’ mother, Esmeralda, took him to the doctor, who prescribed him orthopedic soles. Six months later, with no noticeable improvement, the doctor doubled down and ordered them another set of soles.

Two years passed, and Luis’ condition continued to worsen. His doctor began asking more incisive questions about Esmeralda’s family history. She revealed that of her eleven brothers and sisters, she had lost four of them, one after the other, with no logical explanation—all at a fairly early age. The doctor, now shocked, explained the grim hereditary calculus of genetic diseases to Esmeralda, and now, looking back, she finally understands why some of her older brothers always stayed in their seats. As one of the youngest children in a large family, Esmeralda had stayed, cared for, and witnessed her brothers’ decline even as her older siblings left the house to form their own families.

Studying medical family history might seem obvious today, but looking back 30 years, DMD went undiagnosed even in the better-funded corners of the United States and Europe. If Esmeralda had understood that her brothers’ premature deaths were caused by a hereditary disease, and that she had a 50% chance of passing on to her offspring, she might never have chosen to have children. “I had three other brothers who were fine,” she says. “And three sisters, who all had children. My oldest sister had four children—all boys—and they were completely normal.” She recalls the conversation with the doctor: “How could I have known? When my brothers got sick…I was just a girl!”

Armando and Esmeralda learned that in San Luis de la Paz, there were no available treatments and no wheelchairs or other assistance devices, denoting a total absence of specialists to help Luis’ family make sense of this evolving disease.

Luis’ biopsy came back positive: “Distrofia muscular de Duchenne.” Armando and Esmeralda learned that in San Luis de la Paz, there were no available treatments and no wheelchairs or other assistance devices, denoting a total absence of specialists to help Luis’ family make sense of this evolving disease.

Luis, Armando, and Esmeralda have been living in their modest, sun-bleached rancho in San Antonio, Texas for four years now. Their street is shaded by tall, majestic walnuts, which the family collects and eats when they’re in season. Armando, who has worked in sheet-rocking and masonry all his life, has a construction job down the road and starts his day early in order to help around the house in the late afternoon and evening.

Happy to be home, he lifts Luis out of his tricycle and into his power wheelchair, and they roll into the house together. Inside, Luis is helped onto the living room couch. Almost immediately, a small white-footed cat with gray and black stripes leaps onto his knees and curls into him. “Varon,” says Luis brightly, smiling from ear to ear. “His name is Varon.”

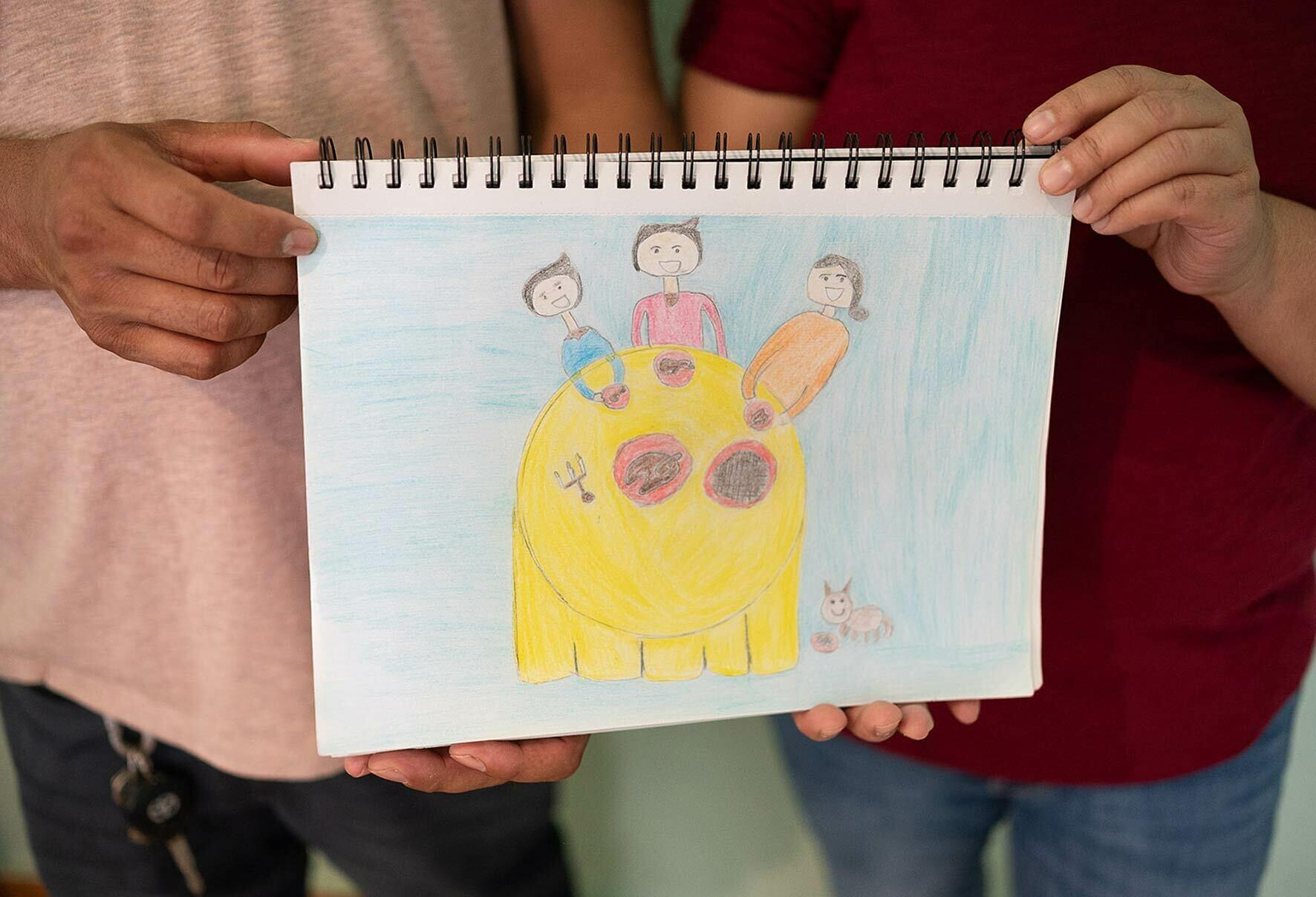

Luis has a kind face— a generous smile, alert eyes, and dark, thick eyebrows. Both he and Armando share a simple buzz-cut; a remedy for the heat. Luis takes a commonly-used glucocorticoid, designed to slow down the onset of puberty and thus DMD itself, but one side effect is severe swelling—his hands, arms, legs, and face are so inflated after two years of steady use that his head is larger and rounder than Armando’s. Despite some of these difficult changes, the family is effectively inseparable. His parents share a drawing he made recently with colored pencils: the three of them seated around a table having dinner; the cat with his own plate on the floor. It is colorful and happy, and in the drawing Luis’ face is mercifully smaller than his father’s.

“Luis is such a happy person,” Esmeralda says. “He’s whip smart. Kind. He has everything. Everything. The only problem he has is Duchenne. He’s always optimistic. He helps find a solution for everything. He’s way ahead of us.”

Cool terracotta tile, sage-colored walls, and the absence of furnishings (to give adequate space for Luis to roam in his wheelchair) lend a tranquil vibe to their home. Some of Luis’ other drawings—a Pokemon character and a boy watching a screen—adorn the walls. The family sits together on the couch on either side of him. Luis reaches his arm over his father’s back and begins to playfully scratch Armando’s neck and tickle his ear.

“Luis is such a happy person,” Esmeralda says. “He’s whip smart. Kind. He has everything. Everything. The only problem he has is Duchenne.” Her jaw clenches. She looks away, wipes a tear from her eye. “He’s always optimistic. He helps find a solution for everything. He’s way ahead of us.”

Luis’ optimism has been bolstered by access to some better treatments and better accessibility devices in the United States. However, emigrating from Mexico was not easy, or cheap. Esmeralda tells us the story about how they came to Texas.

Like so many other young men in struggling Central Mexico, Armando spent long stretches in El Norte (the USA) on construction jobs: in Florida, Arizona, California, and Texas. He was away for most of Luis’ infancy, returning every few years for a few months at a time.

After Luis’ biopsy revealed his illness, it became obvious very quickly that the resources for treating DMD in San Luis de la Paz were woefully inadequate. The family decided that moving to the US was their only course of action—it was very expensive, but they were able to pull it off. “Money comes and goes,” says Armando. “The most important thing is family.”

Luis turned nine years old as they moved to San Antonio—just as his mobility began to contract rapidly. Faced with this new challenge, the family was elated to discover a wealth of resources for treatment and accessibility in Texas. Their house is equipped with a power chair, a stander for his physical therapy, an adjustable bed, and a lifter to help Luis get out of bed in the morning.

Luis’ memories of Guanajuato are more about a person than a place. He remembers his Abuelo, who owned a horse named Vago and taught Luis how to ride him. Abuelo let him watch cartoons on his TV, and at night they slept together in the same bed. “I felt very happy being with him,” Luis says, remembering. Sadly, in September 2020, Abuelo passed away from COVID-19, making the memories all the more precious and fleeting.

“I was depressed for a long time,” Esmeralda shares. “I felt a lot of guilt. That it was my fault for Luis being like this. But I’ve learned more about Duchenne. Seeing so many other people experiencing the same thing…”

As we move down the hallway to Luis’ bedroom, the large, square tiles along the way are cracking under the weight of his wheelchair. One can see a new row of tiles, lighter colored than the originals, where Armando has already replaced some of the broken ceramic. Varon is curled up in his bed now. On the walls are all the trappings of a normal childhood: Fortnight and Naruto posters; an honor roll certificate from school; a string of four silver letter-balloons spelling out LUIS, from his recent birthday party.

“I was depressed for a long time,” Esmeralda shares. “I felt a lot of guilt. That it was my fault for Luis being like this. But I’ve learned more about Duchenne. Seeing so many other people experiencing the same thing…”

She stops and wipes another tear from her eye. “But I can’t stay depressed when my boy is so positive. He knows so much more than us. He understands everything about Duchenne, what it means.” As she talks about him, Luis puts his arm around her. “Luis leads us here. He picked up everything so quickly when we moved to Texas. He translates for me and makes sure I understand what’s going on. Seeing how intelligent and healthy and capable he is—I have to fight for him. Find whatever treatment is available and get it.”

The family does a lot of things together. They are all soccer fans and love watching matches, or putting on a movie in their living room. They listen to rancheros and norteño music and dance in their kitchen. The pandemic has cut off a lot of Luis’ opportunities to be social with others, but his family is always around him.

“I’ve learned how to persevere,” Armando shares. “How to just keep moving forward in life.” He wishes he could have known sooner about Luis’ condition. And he wishes they could have had more children. “A whole soccer team full of kids,” he jokes.

It’s 4:30 P.M. and Luis has been patiently awaiting the treat Armando brought home. With an ice cream cone conveniently in one hand, Luis reaches for a controller with his other hand—time to play his Nintendo Switch. Armando helps him into his motorized wheelchair and Luis suits up with his gaming headphones and controller. A moment later, the cat is back on his lap again. Cat, cone, and videogames pretty much sums up the rest of the afternoon for Luis, an air of contentment filling his heart and his home.